Your cart is currently empty!

Diagnosing and Assessing Processed Food Addiction

Proper diagnosis and assessment from a professional practitioner are the keys to addiction recovery. A health professional can only develop a recovery treatment plan with an adequate diagnosis and assessment. A client cannot track the value of taking action without an assessment. Starting with an accurate assessment is the key to getting the appropriate help for the epidemic of processed food addiction. To diagnose processed food addiction, this blog post uses links to the gold standard texts on addiction.

The thresholds specified in the DSM for a use disorder are two to three symptoms for mild, four to five for moderate, and six or more are considered severe:

- Processed foods are consumed in larger amounts than intended.

- There is a history of unsuccessful efforts to cut down on processed food.

- Much time is spent on activities necessary to obtain processed foods, consume processed foods, or recover from their effects.

- Craving to consume processed foods.

- Recurrent processed food consumption failing to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home.

- Continued processed food consumption despite having persistent social and interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of processed foods.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up because of processed food consumption.

- Processed food consumption in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical ailment likely to have been caused or exacerbated by processed foods.

Tolerance, as defined by either of the following:

- A markedly increased amount of processed foods is needed to achieve intoxication or the desired effect.

- A markedly diminished effect with continued consumption of the same amount of processed foods.

- Withdrawal syndromes without processed foods or eating to avoid withdrawal symptoms.

Challenges In Diagnosing Processed Food Addiction

Developing a diagnosis and assessment will face numerous challenges. First, the processed food addiction assessment is in its infancy. Although various assessment tools have been proposed, they do not necessarily address processed food addiction as a substance use disorder with many manifestations. They may need to be more aware of their use. Addictive foods and cues are at the heart of processed food addiction. As the food system changes to feed all humans, so will the foods we access.

Secondly, diagnosis and assessment for processed food addiction need to cover a wide range of dysfunctions. They can include physical, relationship, financial, career, and family problems. Dysfunction can happen over different times of our lives. Affecting our lives as symptoms of cognitive impairment and mood disorders. A client might be experiencing cravings continuously and spending days seeking, eating, and recovering. Overwhelming their ability to do important things. A complete picture is crucial to developing a sufficiently comprehensive treatment plan and motivating a client to see a need for treatment.

Weight Loss Success Might Cure Processed Food Addiction

Another factor in assessing processed food addiction is that the addiction may have been diagnosed as a weight-loss problem. The client may have experienced multiple failures at “weight loss” as a result of the misdiagnoses. Thus, the client may fear failure in yet another “weight loss” program. Reframing the problem as an SUD is some practice for the health care provider but could be the key to persuading the client to try again and to use different methods to put the disorder into remission. The assessment can be important in diverting attention from weight loss to more serious impairments such as mobility, fatigue, metabolic syndrome symptoms, and executive function loss, by describing the potential to recover from ailments. Each one is well beyond the scope of weight loss.

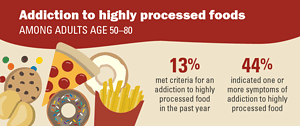

Finally, practitioners may need help accepting that processed food addiction is common. The condition does not necessarily correspond to weight status. Practitioners may benefit from developing a profile of behaviors that conform to the DSM 5 SUD criteria. A skilled and experienced practitioner can probe for addictive behaviors that could otherwise escape notice.

Practitioners can be tempted to dismiss results at the minimal and mild end of the scale. Addictions are progressive, and in the case of processed food addiction, intense pressures in obesogenic environments can accelerate the condition. Aggressive treatment, even in mild cases of pre-addiction, can be warranted.

Prevention strategies

Selective prevention strategies can be applied to at-risk groups for developing processed food addiction. If clients from these populations have not yet manifested clinically significant symptoms. These would include clients with a history of:

- Drug abuse.

- Family history of eating disorders.

- Metabolic syndrome.

- Childhood abuse or neglect.

- Mental or emotional illness.

- A history of weight cycling.

- Availability of processed foods in the home.

- Interpersonal violence.

- A profile of undereducation/poverty.

Prevention applies to clients who are eating processed foods routinely but are not yet manifesting behaviors that would justify a diagnosis when assessing processed food addiction. Clients diagnosed with diet-related diseases who do not require medication could be considered for indicated prevention. Worsening metabolic symptoms such as prediabetes, rising hypertension, or elevated lipids could also be considered for indicated prevention. Even slender clients can benefit from indicated intervention if they are experiencing cravings or instances of loss of control.

The Practitioner must follow diagnostics to assess the consequences of processed food addiction fully. Western cultures have framed the problem as one of weight loss for so long that practitioners are only sometimes accustomed to probing for the full extent of consequences. Ironically, when the full force of processed food addiction is recognized, excess adipose tissue becomes a secondary concern. For example, an article on aspartame, a sugar substitute, has been linked as a possible cause of cancer.

Research has begun to consider whether excess fat tissue is the problem it was once thought to be. Weight may take a back seat to cognitive impairment, depression, fatigue, and mobility. We only have a few decades of experience with processed foods linked to weight gain. These non-weight issues may have more significant outcomes.

The Processed Food Addiction Diagnosis VS. Other Diagnosis

Practitioners may use an eating disorder diagnosis and miss the processed food addiction as an SUD. These diagnoses may include binge eating disorder (BED), bulimia, and anorexia. In the model for assessing processed food addiction, the binge eating disorder diagnosis does not entirely fit why binge use of addictive substances is not a diagnosis in the DSM 5. No addictive substance includes a diagnosis of bingeing. However, binge eating disorder has been shown to worsen processed food addiction, so it is useful to establish whether the client is bingeing instead of grazing. Thus, it remains an important construct to assess. Practitioners will want to discover whether the client is bingeing on processed or unprocessed foods. Bingeing on processed foods can be seen as a SUD. Opposingly, bingeing on unprocessed foods may be considered a separate disorder that could be treated similarly.

Bulimia And Processed Food Addiction

Bulimia may be considered an attempt to compensate for processed food addiction. It is also associated with more difficult outcomes and should be described in the assessment. Likewise, anorexia may also be an attempt to overcome processed food addiction. In any eating disorder, there is compelling evidence for the harmful properties of processed foods, particularly their role in the development of neuro anomalies. Thus, processed foods should be avoided in the treatment of eating disorders.

Although there is research on the validity of the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS), there is some evidence that it is not measure processed food addiction as a SUD but as a behavioral disorder such as shopping, gambling, or sex. The scale operationalizes the DSM 5 SUD criteria. However, processed food addiction has many manifestations, some missing from the Yale Food Addiction Scale.

For example, the Yale Food Addiction Scale identifies dangerous use as eating or thinking about food while driving a car. However, food-addicted clients may also eat spoiled food and burn themselves eating too hot or frozen foods. Clients may also run the danger of blacking out while driving. Research shows they are prone to accidents due to joint balance issues, excess adipose tissue, and the inability to see their feet. The Yale Food Addiction Scale does not surface these possibilities. So, the Yale Food Addiction Scale may be underdiagnosed. It needs to include more of the range of manifestations of the pathology.

The Yale Food Addiction Scale

As another example, the Yale Food Addiction Scale asks about avoiding social events for fear of the foods that will be there or fear of loss of control. However, clients may also avoid social events due to fears related to weight and not fitting in. These possibilities are not included in the Yale Food Addiction Scale.

It is easy to confuse processed food addiction with modern-day eating behaviors. To maintain clarity, practitioners need to remember that in assessing processed food addiction, eating is just a means for absorbing addictive substances. Eating for the food-addicted client is no different than drinking for the alcoholic, snorting for the cocaine addict, smoking for the nicotine/cannabis addict, or injecting for the heroin addict. This concept may help practitioners to focus on addictive substances. Instead of being distracted by the fact that the substances are being eaten in many forms.

Probing For Subilties And Severity

Two thoughts may stand out to practitioners as they read through DSM 5 SUD criteria descriptions. First, it is easy to miss the subtleties of processed food addiction and, therefore, to miss the development of a severe condition. Many addicts minimize the use and its consequences. Food-addicted clients are no different. Clients may suffer from memory loss. Practitioners would benefit from probing and listening carefully for the nuances of food-addicted behavior. Asking about foods used in each criterion also helps to jog memory.

Overeating is so common in obesogenic cultures that practitioners have a temptation to dismiss aberrant eating behaviors as normal. Recalling that cigarette smoking was “normal” at one time may help practitioners categorize food-related behaviors as pathological, even though the behaviors may be very common. Considering the vast quantities of addictive foods that disappear into the US economy, practitioners may ascribe importance to behaviors that many consider benign. A smoker in 1960 would not be identified as problematic. However, a smoker in 2023 would be. Similarly, instances of losing control over eating in 1930 during the Great Depression could reflect anxiety about food shortages. However, in the obesogenic environment of 2023, loss of control could indicate the beginning of an addictive relationship with processed foods. In short, practitioners would do well to consider the obesogenic culture in which the assessment takes place.

Secret Ingredients Added For Addictive Qualities

The second point that may surface from reading the SUD criteria is that, in some cases, processed food addiction could be a more serious addiction than drug addiction. The assessment for the severity of processed food addiction can easily be compared with drug addiction. Food-addicted clients may have experienced processed food addiction as young children. This is as opposed to drug and alcohol addicts, whose earliest experiences may be as adolescents. Drug addiction rarely starts in adulthood. Drug addicts may combine one or two addictive substances, whereas food-addicted clients are likely to combine all the major categories of addictive foods routinely.

Food manufacturers may be formulating foods to be particularly addictive, using ingredients that are unknown to the public. Further, the reminders in advertising and availability of processed foods are intense in Western cultures, far exceeding that of drugs of abuse. If an unexpected number of severe cases occurs, practitioners can treat them as such.

Although it may seem uncomfortable to inform a client of a finding of severity, practitioners may be surprised that clients accept the diagnosis with relief. After grave suffering for decades, clients may be grateful to find a solution. They may already suspect that they have a serious problem. They may be glad that a practitioner is taking their problem seriously and helping them devise a comprehensive plan to manage the problem.

Using The Addiction Severity Index

The Addiction Severity Index defines a list of practitioner options for clients. This helps the practitioner and client decide where to start in the development of a comprehensive recovery program. For example, the assessment considers how much the client must be around addictive foods to fulfill life obligations. Processed foods and drinks are used throughout the day in various social, business, school, and faith-based situations. If clients are exposed to extensive reminders, they may have to make lifestyle adjustments before producing clean food. In some cases, cue-avoidance strategies may need to be in place before the client can quell cravings enough to choose healthy foods, including nuts and vegetables. Clients may only need to avoid reminders for a few months while the reward pathways in the brain are reduced.

The Addiction Severity Index also helps define frequency measures. Processed food addiction behaviors can be virtually continuous throughout the day for a client. Following this introduction, some DSM criteria may be experienced by clients simultaneously and frequently throughout the day. Practitioners can ask clients how often they experience SUD symptoms and give the client the option of answering continuously. This helps the practitioner see the degree of compulsion the client suffers.

Addiction And Relapse

Similarly, if the client has been exposed to stressful situations, starting a clean food routine may be unrealistic. Almost every hospital, school, and prison depends on offering a menu of processed foods. All three are places of great stress for most people. Stress, particularly relationship stress, is a known relapse trigger. If stressful relationships occur inside the client’s home, the client may need to learn and practice defensive relationship strategies before starting a food plan. This is especially the case if addicted children are present in the home. A financially devastated client may need budgeting skills to start a nonaddictive food plan. The ability to effectively prioritize approaches depends on a comprehensive, in-depth assessment.

SUD diagnostic categories

Hopefully, the drug counselor and general health practitioner will feel at home with the similarities between assessing processed food addiction and classic drug addiction. This concerns conformance with the DSM 5 SUD diagnostic criteria and the Addiction Severity Index. Eating disorder professionals may have clients who are unfamiliar with these criteria but familiar with the problems of treating eating disorders. Eating Disorder Counselors can categorize known eating disorder symptoms into the SUD diagnostic categories.

Counselors may find that some clients have impairments of such a wide variety that if they were drug addicted. Residential treatment would be recommended. However, insurance coverage for processed food addiction is nonexistent, and eating disorder clinics may be unwilling to support the client. The abstinence of harm reduction protocols when assessing processed food addiction is challenging for healthcare professionals. Many clients cannot afford to go to residential facilities for lack of funds and obligations to jobs or families. Regardless of severity, some have drug and alcohol addiction. Nonetheless, a severity finding based on the number of DSM 5 SUD criteria met could encourage the client to build a more comprehensive program at home, as would be the case without a comprehensive diagnosis. A variety of treatment resources can be found at https:thefoodtrust.org/resources/.

How food addiction and drug addiction are different

Dissimilarities of processed food addiction to drug addiction are found in the young age of onset, prevalence of cues, easy availability, and polysubstance nature. Asking clients about their first memories of cravings or food obsession will quickly show practitioners that most clients meet this criterion for severity with the age of onset starting as young as toddlerhood.

Practitioners may be uneasy with assessing for exposure to food cues because of the prevalence of triggers for the client. Of course, it is impossible to avoid processed food cues. However, cue management can be accomplished slowly and through education about the seriousness of exposure to food cues. Missing the extent of sequencing in a client’s daily routines could undermine an otherwise sound program.

Many Ingredients For One Addiction

The polysubstance nature of processed food abuse can be understood from the book Abstinent Food Plans For Processed Food Addiction. Sweeteners, flour, gluten, salt, processed fats, dairy, and caffeine are consumed in great quantities in Westernized cultures and almost always in combinations. Fast food products can combine all addictive substances with flour and gluten in a bun, taco shell, or pizza crust. Sugar is an ingredient in sauces, French fry coatings, and drinks. Cheese and processed fats are added to virtually everything, and caffeine is in the drinks. A quick question about what the client ate and drank for breakfast will surface these combinations. Addictions that use multiple substances are harder to treat. Practitioners can use this research to persuade clients to build sufficiently comprehensive programs of abstinence, cue avoidance, cognitive restoration, and group support.

Of course, even with an appropriate diagnosis and assessment, practitioners know that addictions are hard to treat. The conditioned vulnerabilities of an addict’s brain lead to a lifelong risk of relapse. In environments where cues are rife, the risks run higher. Recovery from processed food addiction suffers from this fact of life. Clients with a comprehensive impairment must learn to make free meals from thousands of addictive ingredients. It is difficult to ask the client to prepare abstinent meals without becoming overwhelmed consistently. With a comprehensive assessment, the practitioner and client can work together to plan a “doable” course of action to yield a sufficiently comprehensive and focused program.

Distinguishing Weight Loss From Assessing Processed Food Addiction

A central purpose of assessing for processed food addiction is to avoid confusing processed food addiction with weight issues. By carefully working through the DSM 5 SUD criteria, the practitioner avoids missing processed food addiction in normally weighted clients. Addiction can be present before enough fat tissue accumulates to become a weight problem. As a corollary, the practitioner also avoids automatically diagnosing processed food addiction in obese clients.

An obese client can be incidentally obese from eating calorie-dense foods readily available in Westernized cultures without developing dysfunctional consequences. This client may need advice on foods to avoid and foods to consume. The practitioner can uncover addiction by relying on the DSM 5 SUD criteria. Even if the Addiction Severity Index assessment does not seem serious, the practitioner can treat addiction aggressively, given the progression consequences. The data gathered from the diagnostic criteria can also be used to help inform an assessment of processed food addiction in children. Those criteria are included in Chapter 30, “Strategies for Helping Food-Addicted Children,” found in Part III of this textbook, “Treatment.” It can be hard to disassociate the degree of overweight and obesity from processed food addiction. Still, dependence on the DSM 5 SUD criteria and the Addiction Severity Index are the keys.

Motivating The Client

The diagnostic and assessment processes will yield valuable data on failure to cut back. Clients are likely to present with a long history of failures to lose weight. They will likely have developed a fear of failure and a reluctance to try again. Practitioners will recognize the discouragement from repeated failures to lose weight. The approach here emphasizes the hope of a new protocol based on the addiction model. With this approach, the practitioner can allay fears built over time. Failure only comes from failing to meet goals within a specified period. So, assure the client that there are no deadlines and the client will have all the time they need to buy into the idea that by going slowly and picking out easy tasks, a solid program can build a dependable program.

Defining The Scope Of The Problem

The role of the assessment is to define the parameters of the target behavior and comorbidities. The assessment is the first stage of delineating benefits from recovery. The practitioner would do well in behavioral, financial, professional, and family management. Like all other addiction assessments, it requires assessing processed food addiction within the DSM 5 and ASI to develop a broad scope of the physical, mental, and emotional pathology associated with very broad impairment.

While it is important not to overwhelm clients, giving them hope for building a lifestyle that yields a broad range of important benefits can be useful. As part of the problem assessment, it is important to ask about mobility and fatigue because they can be barriers to meal preparation and exercise, which are important elements of recovery. Asking about sleep quality is helpful, as sleep can significantly impact cognitive functionality. Only if the practitioner has the training to assess cognitive functioning it is important to do so with and without the presence of food cues. This may motivate the client to remove processed food from the home and avoid making decisions in the grocery store. Assessing impaired cognitive abilities will help create realistic expectations for early-stage skill acquisition.

Relapsing And Reminders Of Processed Foods

Reminders of processed food are a leading problem in relapse avoidance. Assessing the client’s unavoidable and elective strategies for processed food reminder avoidance in their daily and weekly routines can help determine how important developing strategies to avoid exposure to reminders. Learning to avoid food reminders may be relatively easy for clients to accept that going into a grocery store is dangerous, just as it would be dangerous for an alcoholic in early-stage recovery to go into a bar. Avoiding the break room at work, the fast food outlets on the highway, and restaurants on Friday night can all be hard for clients to accept.

If the client has minimal food preparation skills, the assessment will surface this important problem. Simple cooking methods, such as filling a slow cooker, will be best. Frying foods is also relatively easy. Setting up a baking tray or filling a soup pot is easy to teach.

Proper Cognition Is Needed To Cure Addictive Activities

Cognitive impairment is a significant problem because of the need to acquire meal preparation and cue avoidance skills. Online brain training, such as Lumosity and Brain Age, may be effective for cognitive restoration. At the same time, the burden of engaging in brain training games is light and flexible, so clients are generally willing to participate.

A surprisingly important problem in assessing processed food addiction is the status of unavoidable stressful personal relationships for increased risk of relapse. If an unpleasant person is in the client’s life, attempting to work a clean food plan may attract ridicule and possibly sabotage. It is important to ask about these issues and offer strategies for setting boundaries. addicted children are likely to endure emotional withdrawals. The client should be prepared for that. Defining the scope of the problem plays a crucial role in the assessment. This is especially true in assessing processed food addiction because of the general focus on excess adipose tissue to the exclusion of the broad range of other dysfunctions associated with chronic abuse of processed foods.

Determining A Diagnosis

The DSM 5 SUD criteria provide a well-substantiated guide for developing a reliable diagnosis. Practitioners may find that processed food addiction is common. The DSM specifies that meeting only two of the use SUD criteria and exhibiting distress within a year would indicate a problem with substance abuse. However, despite knowledge of consequences, many might meet at least four SUD criteria of failure to cut back, unintended use, cravings, and use. As practitioners gain experience with the 11 HUD criteria, they may be surprised at how many obese people meet all of them. At the other end of the spectrum, it may be hard to find anyone who doesn’t meet the criteria, especially use despite knowledge of consequences.

After years of failing to conform to weight-loss protocols, clients may feel relief to get an accurate diagnosis. Sharing a diagnosis and its severity with a client may increase the determination to put the disorder into remission. Practitioners can explain the severity of addiction translates into an increased risk of relapse. Understanding these concepts is important in the development of treatment. Because of the prevalence of processed food cues, the common use of processed foods in Westernized cultures, and the stress of restructuring relationships, correctly assessing severity is important.

An accurate severity assessment must determine the extent of cue avoidance, abstinence, cognitive restoration, energy, relationship repair, physical recovery, etc. Underassessing severity can lead to a program too weak to keep the disease in remission. Overassessing can lead to unnecessary and unrewarding changes in lifestyle, which can erode confidence in the program. An accurate assessment of severity is vital.

The ASI helps practitioners identify:

- Other psychiatric diagnoses and problematic psychological states include depression, anger, anxiety, and shame. The range of severity can run from mild to suicide ideation, rage, and panic.

- Physical diagnoses including diabetes, heart disease, joint impairment, hypertension, and excessive adipose tissue.

- Mental diagnoses including ADD, ADHD, memory loss, poor decision-making, poor impulse control, and inability to achieve satiation.

- Behavioral problems including hiding food, bingeing, starving, purging, disrupted sleep, night eating, and lethargy.

Developing Outcome Expectancies

Practitioners should outline outcome expectancies in the assessment. The emphasis should be on mental health over weight loss. Clients should be able to connect the full spectrum of diet-related diseases to processed foods. Practitioners should discuss adjusting to a non-obese body in terms of sexuality and attractiveness. Heightened relapse risk should be delineated and tied to the number of DSM criteria met, young age of onset, the prevalence of cues, polysubstance use (sugar, gluten, salt, processed fats, dairy, caffeine, additives), and ready availability of cheap, convenient, fast foods. The practitioner should explicitly reference meal preparation skills, either as not needing much attention in the case of skilled clients or needing to go slow and develop simple meal preparation routines in the case of inexperienced clients. The ability to shop for, cook, and assemble meals of nonaddictive, unprocessed foods is crucial to success.

Planning is a separate skill that the practitioner can monitor. The ability to schedule on-time meals in the context of a busy life is also a skill that clients may need to improve. The practitioner can motivate the client to develop meal preparation skills by offering valuable outcomes such as improving diet-related diseases, fatigue, depression, and cognitive abilities.

Self-efficacy is an arena that the practitioner will want to explore. Clients can build a belief in their ability to succeed. In recovery from processed food addiction, much depends on attracting the client to the addiction model and away from the “weight loss” model. It is helpful for the client to commit to taking the recovery process slowly to eliminate the possibility of failure.

Determining Readiness To Change And Readiness For Treatment

The stages of readiness for treatment of processed food addiction are similar to those of drug addiction. The personalized feedback derived from the assessment process facilitates the motivation to change. Stages of readiness are covered in detail in Part III of the textbook, “Treatment,” and include:

- Reasons for change

- Problem recognition

- Optimism about change

- Commitment to change

- Action

- Maintenance

The assessment plays a central role in identifying the reasons for change and the process of recognizing the problem. Based on the assessment’s strategies, the practitioner can work through the client’s concerns about making the change and build optimism and commitment. The treatment plan, as developed from the assessment, serves as a guide for the long, slow process of disengaging from signals to eat processed food, restoring cognitive function, developing a routine for meal preparation, setting boundaries in relationships, exercising and sleeping regularly, and becoming situated in a support system.

How Much Is Enough? Balancing Scope Of Assessment With Cost And Utility

Although extensive assessment would yield valuable information, conducting full assessments is often not practical or cost-effective. However, developing the client’s status according to the DSM 5 SUD criteria could yield enough information to persuade a client to the processed food addiction model, motivate a client to undertake recovery, and lay out options to start recovery. Creating a baseline of problems organized by the DSM 5 SUD criteria is enough to track progress and encourage the client to keep building a recovery program.

If resources are available, it would be desirable to run a full physical to gather information about nutritional status, hidden needs for medication, and range of mobility. A full physical could impact treatment in the referrals to specialists. When assessing processed food addiction, mental capabilities could determine whether the client can decide in a grocery store or needs to engage in a shopping service. An assessment of mood would demonstrate the client’s ability to manage difficult relationships as well as the ability to care for themself. An in-depth review of the DSM 5 SUD criteria could take many visits. Each criterion could surface a long history of multiple dysfunctions. However, this textbook considers that clients are likely to be of limited means, which points the practitioner toward a single-visit data-collection effort based on the DSM 5.

Despite limitations, getting comprehensive information to develop a treatment plan would require more than just the DSM data. Collect information for a treatment plan in subsequent visits.

Timing And Sequence Of Assessments

Periodically, reassessing clients has significant benefits in keeping the client on track. This is particularly true for processed food addiction in an environment where competing nutritional and weight-loss ideas are often pressed on clients by media, health professionals, friends, and family. Clients will gain motivation to stay on track by periodically reviewing progress. A periodic review reinforces the many connections between processed foods and diseases.

Initially, it may be hard for clients to believe that many problems could be associated with processed foods. The media must broadly disseminate these connections, which depend on the food and medical industries for advertising revenues. Medical personnel typically need to become more familiar with diet solutions to ailments. Getting an education in pharmaceutical and surgical solutions to health problems. So, in assessing processed food addiction, the counselor has the pleasure of sharing in the unexpected remission of a broad range of physical, mental, and emotional behavioral problems.

Memory Loss And Diet Changes

It is important to remember that clients may be suffering from memory loss. So, bringing benefits to mind enriches recovery and makes the recovery more valuable to the client. Also important is that recovery occurs in an environment rife with friendly food pushers. In short, the client can use a periodic rearming with reasons not to take other advice nor cave to a bite here and there. Information about the many benefits of recovery protects the client against the pressures of an obesogenic culture.

Clients who come into recovery with severe cases may need follow-up more often. The severity is demonstrated by a long history of attempts to lose weight and may be challenged to let go of inappropriate information. Clients may still experience the urge to restrict calories, eliminate fats, protein, or carbs, fast, overexercise, expose the brain to heavy cueing, undertake harmful surgery, use sugary meal replacements, and process foods at home in food processors. Periodically touching back to the assessment can help clients remember that not only did these approaches fail, but they could possibly have worsened the processed food addiction. The reassessment timing can be based on the severity of overeating, risk of relapse, and consequences.

Interviewing Techniques And Styles

Motivational interviewing emphasizes empathy and supports client autonomy in discussing As with all addictions. Motivational interviewing is appropriate for food-addicted clients. Whether changes would be worth making. With this approach, practitioners can avoid power struggles and persuasion in favor of developing the client’s reasons for undertaking recovery. The style is to use the information collected in the diagnosis and assessment to explore the client’s concerns rather than try to persuade the client that treatment is the only option.

Practitioners will want to be respectful and patient throughout the diagnostic and assessment processes. Adopting a motivational style that is nonjudgmental and supportive will help. Practitioners will remember that clients suffer from memory loss and that recalling events, foods, and behaviors be difficult. For the same reason, practitioners may need to repeat information. Handouts will help reinforce auditory information. Food-addicted clients also suffer from shame and may not be able to share about embarrassing situations, particularly around bingeing, perceived failures, and difficult relationships.

Practitioners may be helpful by reassuring clients that their situations are not their fault. Rather, an aggressive food industry has deliberately formulated and marketed products to be addictive. Explaining why weight-loss regimes could worsen processed food addiction helps clients reduce self-blame and confidently move forward.

Treatment Planning And Matching Clients To Treatment

The assessment will surface strategies for building a program of protection against relapse into the use of addictive processed foods. Programs have to accomplish many different complex objectives. These include meal preparation, cue avoidance, cognitive restoration, exercise, sleep, education, disease resolution, and relationship management. The initial stages of treatment can focus on the slow but steady development of skills to realize goals. The key challenge is how to sequence goals. The solution is to let the client pick from a list of options. The practitioner can develop the options based on the problems that surfaced in the assessment.

The practitioner can also point out the strengths of the client. The client can start with strengths in terms of comfort level with cooking skills, exercise, cognitive restoration, cue avoidance, etc. Advanced issues are similar to recovery from drug addiction and include relationship repair, financial stability, employment, and volunteer service activities.

Avoid Overwhelming With A Menu Of Small Steps

Clients could easily feel overwhelmed. They might be prone to quitting if presented with too much. The menu could include starting with mental, physical, behavioral, or food issues because of limited information. Slow but steady wins the race.

A special thank you to Brian Clement for his book, Food Is Medicine.