Your cart is currently empty!

The History of Dried Fruit Farming in Vacaville California

Why Farmers Count On Drying Fruit

When there was a glut of ripe fruit to ship or when fresh fruit prices fell during the season, farmers cut and dried some of their harvests. Dried fruit farming kept well and, therefore, could be stored until prices rose later in the year. At a time when fresh fruit could not be stored for long periods and remained a seasonal delicacy, dried fruit was a popular alternative to fresh fruit.

“When you went to a restaurant years ago, stewed prunes were always on the menu. Nowadays, very few restaurants have it,” said dried fruit producer Richard Nola. Dried fruit supplemented diets and was a mainstay for soldiers during both world wars. Its high sugar content made it a welcomed sweet snack.

Dried fruit from the Vacaville and Suisun Valley areas proved popular in Europe since its quality surpassed that of products from countries such as France. Around 1897, the Ernst Luehning Company of Hamburg, Germany, decided that running a drying and shipping house in Suisun was profitable, shipping exclusively to the European market.

A California Community Rises From Growing, Cutting, and Drying Fruit

During the heyday of the fruit industry, most ranches operated their dry yard, employing hundreds of men, women, and children throughout the season. Women and children usually cut the fruit and arranged it on the trays. For many teenagers, summers cutting fruit were rites of passage. Men built the lug boxes, lifted the filled boxes, stacked the trays, and carefully laid them out in the dry yard. Dipping wire baskets filled with prunes into a bath of water and lye to help break up the skins in preparation for drying was another male task. They also ran the sulfur house, where apricots and peaches underwent 24 hours of sulfuring before being set out to dry.

In the 1920s, three-quarters of the orchards were converted to prunes. New varieties, such as the Burton prune, were developed locally. This popular prune, with especially high sugar content, was so large it was difficult to dry in the sun, leading to the installation of the first dehydrator in the Vacaville area by J.N. Rogers in 1920. Several other orchardists followed in the next few years. One of the best-known was the dehydrator installed in 1926 by C.J. and Ed Uhl. With the motto “Eat ‘Em Like Candy” on the label, their boxes of bulk-dried fruit were welcomed gifts in many households.

Industrialization Comes To The Central Valley Of California

Eventually, commercial firms did most of the dehydrating, something farmers found more economical. The oldest continuously operated dehydrating company in the area today is the Vacaville Fruit Company. Established in Vacaville in 1944 as Danielson & Bowers, it became Abinante & Nola before obtaining its present name.

The modern dry fruit market is waning because of the changing eating trends of domestic customers and heavy competition from foreign countries. Still, many local growers remember when, as rancher Roy Mason put it, “Every ranch had a small dry yard. They would dry some apricots, peaches, pears, and prunes. It kept people busy all summer.”

After the fruit was picked, it was brought to the cutting sheds. Her children aged five and up, young girls and women could be found from sun up to sundown, standing with a knife in hand cutting the ripe fruit. “We had little tables where you would put the fruit trays;’ continued Mason. “You’d put the boxes of fruit by the side of the tray, and you’d stand there cutting fruit and laying it on the trays.”

Lola Nofuentes Moriel And Her Son, Jim, Explain The Process Of Drying Fruit On Their Family Ranch.

Jim Moriel Sr. farmed not only their ranch but also leased property. According to his wife, Nofuentes Moriel, “We brought the fruit from all the ranches to the cutting shed at home, maybe 100 boxes at a time. Jim and his father would unload the 40-pound lug boxes. One year, we had 40 dry tons of bulk apricots. The ratio of the fresh to dry is about five to one.”

Nofuentes Moriel oversaw the cutters. “One year, I had 60 cutters. Every year the same children made their application for the following year, so I guess we treated them pretty well. The standards we had then were sanitary. The cutting shed had a cement floor, and my cutters had to wear hairnets.

“There Would Be Between 10 And 15 Trays Going At A Time. These Were Called ‘Stations.’ There Were Three Or Four People Per Tray. Two On Each Side”, She Said.

One tray would fit on a waist-high table. Moriel added, “We’d stand one box up and put the full box on top of chat for height. When the tray was full, then you put another tray on top. That is why they started off at a reasonable height so chat four or five trays could be stacked, and cutters could still reach across the tray.

“We paid the cutters by the box. When a cutter finished their box, they would holler, ‘Fruit.’ Each cutter had a ticket, and the ticket would get punched as they finished a box. They were paid 25 cents a box. The cutters were paid less per box of peaches than for apricots because the peaches were bigger and fewer in a box. When the full trays were stacked four or five high, two strong men would carry off the full trays. Many ex-military soldiers after WWI headed to California to be employed in fruit farming.

Nofuentes Moriel, meanwhile, had to be on the lookout. “There was some chat that was slick and would cry to get an empty box, so I used to go from tray to tray and check.” Other cutters were dedicated. “During the time another person and I were carrying the trays out, the more motivated ones continued to cut into their box.”

The Work Of Fruit Cutters In California

People gained reputations as fruit cutters. “We had some good people,” said Eva Yee Palm. “One of them was Mrs. Lozano. She was the fastest cutter, and she was a perfectionist. She was an efficient fruit cutter. Very coordinated. There is an art to cutting fruit.”

Yet, she added, “You could have problems with cutters. You can tell them over and over and over, and they don’t do it right. They might cue the fruit halfway and pull the thing apart. They might leave the pits in the fruit. When you put fruit on the tray, you can’t put another one on top.”

“Speed Was Always Essential, And Many Cutters Prided Themselves On Being Fast.”

Jean Hoskins Callison recalled from her days in the family’s cutting shed, “I was about 15 when I started cutting fruit. Cutting peaches was a big job. My table partner was a girl I went to high school with. My goal was to cut as fast as she could. I missed it every day by one box. Dorothy cut 50 boxes a day. I was always about 49. It was just the right snap of the wrist. One cut and flip the pit with your finger as you put it on the tray.” The pits were flipped back into the box with the uncut fruit.

Lola Nofuentes Moriel worked with her cutters to advance their skills. “I would also cut apricots from their boxes and show them how to set the fruit level on the tray. We used to show the kids how to turn the fruit from the seam and how to throw the pit out, all in one motion. Farmers wanted nice clean cuts. Some cutters used to spit chat pit like nobody’s business. Just circle it, and the pit comes right out on the last cut. You grab another apricot with one hand, and with this one, you are setting two halves down.”

Sometimes there were accidents with sharp knives. Marcus Lopez, who started cutting early, recalled: “Everybody had his or her knife. You grab the apricot between your index finger and thumb and hold it in your palm.

“The Whole Idea Was Don’t Slice Your Palm, Which I Have Done More Than Once, And So Have Other People.”

You do that a few times and are a little more careful afterward. Sometimes people would set the ‘cot down with the knife in their hand, and sometimes they got cut if somebody else was setting it down. A first-aid kit was standard equipment in the cutting sheds.”

“I would send them to wash their hands and then to the sulfur bag to dip their finger in there.’ added Lola Nofuentes Mariel. “None of them got infected. There is something about sulfur that used to heal them.”

The Apricot And The Central Valley

One of the main fruits cut in Solano County was the apricot. “The ones that looked the best were the circular ones, all nicely formed,” noted Jim Mariel. “That was quality, and that’s how you’d get paid. The ‘cot needs to be set on the trays flat, so they don’t leak because they tend to fill up with juice as they dry.” Learn about the entire process of drying apricots here.

Eva Yee Palm elaborated: “You have to put the fruit on the tray real close to each other, and you can’t have them tip on their side because after you sulfur it when all the juice comes up, you want the juices to stay in the cup of the fruit.”

Pears also were cut, sulfured, and dried, particularly in Suisun Valley. Lin Tim Lowe remembered, “The better pears were packed fresh and shipped east. What they left behind, they called those culls. They would spread rows of them under the almond trees and put straw over them until they ripened. Then they were brought in to be cut.”

“Pears were the hardest to cut,” said Peggy Bassford Byrd.” You had to pick the stem out, and then you had a little scooper to scoop the middles out. Usually, you worked in pairs; one cut and the other scoop. Unlike apricots and peaches, when you lay them on the tray, it wouldn’t matter which side was up”.

Marjorie Ridenhour Wildman also cut pears. “For pears, a different knife was used. The pear knife, the handle was just a little bit heavier.”

The Nira Fong Wong’s Family – Known For Inventing The Pear Knife

Nira Fong Wong’s family is credited with inventing a special knife for the pears. Until then, the hooks and knives had been separate.” In 1938, my dad invented a knife with a hook, which made it easier and faster to cut the pears,” she said. “My dad made hundreds of those knives for the cutters”.

At the Vacaville Fruit Company, pears are being dried today, but not local pears. Richard Nola explained why. “We don’t take pears from Suisun. They’re picking the pears in Suisun on the 20th of July. In Lake County, they will not start until maybe the 10th or 12th of August. That additional three to four-week growing period puts more sugar in the fruit. That makes a better-tasting dried pear and recovery ratio better.”

Transportation Of Product In Nut And Dried Fruit Farming

Most ranches had a miniature railway system with small tramcars running from the cutting shed to the sulfur house and then out to the dry yard. The tracks were pieced together so the route could be changed at will. These cars were first put into operation at the cutting shed. The trays full of fruit were removed from the cutting tables three or four at a time and stacked on the rail cars. “When the trays were stacked 22, 23 to a car, they’d push the car on the rail out to the sulfur house and put them in there,” said Roy Mason.

On the Mariel Ranch, they discarded the rail system in favor of a trailer. A tractor drove through the sulfur house, pulling it. Once in the sulfur house, the trailer would be unhooked and left there. Larger ranches might have more than one sulfur house. The Moriel Ranch had four. “There would be three stacks, 30 trays high on the trailer,” said Jim Mariel. “That means each trailer would hold 90 trays.

“A Filled Trailer Represents About 300 Boxes Of Fruit.”

Another name for the sulfur houses was “bleachers.” Made of wood, the bleachers were about six feet tall and had a small opening at the top of the door. “The bleacher would hold as many trays as you wanted to stack up, higher than my head,” Rose Crabtree explained. “You would close the oven and burn about two shovels full of sulfur in a little pit in the bottom. You’d keep the fruit in overnight. That seals the fruit and makes it bug-repellent.”

Roy Mason said, “They let the sulfur burn for eight or 10 hours. As the fruit cooked, the juices would come to the top. This is why it was so important to lay the cut fruit flat and cut it all the way around, so it wouldn’t have any tears where the juice could leak out.” Leaving the juice in the fruit cup added to its taste and suppleness when dried.

Jim Moriel explained the chemical process. ” Burning sulfur causes hydrogen sulfide, which bleaches or cooks and sanitizes the fruit. It makes the fruit a beautiful color when the sun gets through with it. For the person who opens the bleacher early in the morning, they get a whole lung full of sulfur. It was a healthy experience. It would clean out your sinus.”

The Drying Of Prunes

Prunes became the foremost crop during the Depression and remain among the major crops in Solano County today. Prunes are handled differently than dried fruits because they are neither cut nor sulfured. Instead, they are dipped in a water and lye solution.

Masako Minamide said it was no easy task. “Prunes were hand-dipped at what we called the dipping location on the ranch. We used butane to boil the water in a big tub. For every 100-150 gallons, they put in a pound of lye. That cooks the prunes instantly. You put the prunes in a big dipper, which is dipped for a certain number of seconds. Then they’d roll down this machine. It’s all motor. There is no electricity out there. The machine shakes as the prunes descend at an incline on the conveyor belt. A screen is there, and all the leaves, little junky prunes, and dirt go out. Water is always falling from the top, which helps cool the prunes.”

That Is Why In The Old Days, When Drying Prunes, They Used Hot Water And Lye In The Water To Check The Skin.

Working with lye could be dangerous, and not everybody knew its dangers. Peggy Bassford Byrd recalled her experience on the family ranch. “When you dipped prunes, you had to have a fire for the vat of lye. You had a big basket, and you dumped two boxes of prunes into this basket and put it down into the lye. They would come out hot and would smell so good. I decided to eat some, and that’s how I took my tonsils out. The lye ate my tonsils. It’s a wonder I didn’t die. I was sick for a long time.”

A prickle board was used to break the skin. Bob Hansen elaborated: “You’d dump the prunes out onto the shaker that ran off an electric motor, which would shake the prunes down to a single layer. Then the prunes were rolled over this fine prickle board and dropped onto the trays. The prickle board would break the skin just enough so that moisture could get outside the prune when it dried without stewing it. The prickle boards were used probably up through the 1940s.”

From there, the prunes were put on the trays and taken out to the dry yard, a section of property usually fenced to keep animals out, according to Peggy Bassford Byrd.

Keeping The California Nut And Dried Fruit Farming Facilities Clean

Dust was an issue in the California climate and must be kept down. “That’s why some would put blacktop wherever they were going to have their dry yard,” said Joe Moreno. “That way, if the wind came up, it wouldn’t get dust all over the fruit.” Other farmers handled the problem the way the Moriel family did. “The dry yard was dirt,” said Jim Moriel, “but we didn’t cultivate, so it was level and more dust-free.”

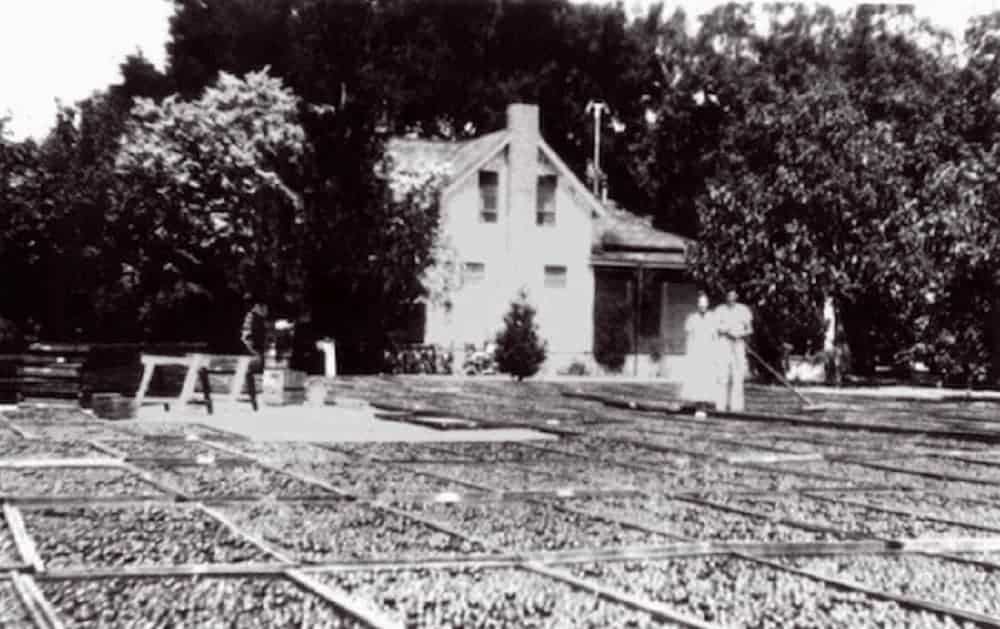

Once in the dry yard, the men would take the trays of fruit off the tramcar, one or two at a time, and lay them on the ground. The bottom of these redwood trays was made of slats rather than solid wood. The trays were tiered out in the dry yard, the edge of one tray set on the edge of the tray behind it. This allowed the hot air to circulate through the bottom of the tray, aiding in the drying process.

Extremely Hot Summers And A Dry Climate, Solano County Has Been An Ideal Place To Dry Fruit

The fruit would sun-dry within one to four days. Because of their thickness, peaches took longer than apricots. On the Samuels Ranch, the Imperial prunes also took a long time to dry.” They had to be turned at certain intervals so the sun reached all sides because they were very large prunes,” said Arlene Samuels. Masako Minamide’s children helped speed up the process. “When the children were small, they rolled the prunes so chat they’d dry on both sides. The prunes will dry because the air comes through the bottom of the tray, but it takes longer. My three kids would do so many rows, which was their daily work.”

Rain was the enemy of fruit drying. Jean Hoskins Callison recalled middle-of-the-night runs with her father, scrambling to stack the trays to protect them. “You didn’t want your nut and dried fruit farming ruined by the rain. When it would rain, you’d make a big tall stack right in the field, then turn an empty tray on top. That protected the fruit well’. Ocher farmers reported similar experiences. “The boss called us while it was still dark’, said John Lowe. “We had to use a kerosene lamp to go out to the dry yard and stack the fruit trays.”

Prune growers were most affected by rain, said Jim Moriel. “Rain wouldn’t hurt apricots. Apricots do not rot when they get a little bit of water. They have been sulfured, so they have been initiated. Prunes are an entirely different matter. Prunes farmers used to have heart failure when it rained. If you let a drying prune get wet, it rots.”

Moving Trays Of Dried Fruit

Once the fruit was partially dried, the trays were stacked and removed from the dry yard. “They didn’t leave them out in the direct sunlight too long, or the fruit would dry out,” explained Lola Nofuentes Moriel. “Stacked, the hot air would get through the trays, which dried them.”

Moving the trays was an unpopular chore, said Joseph Saito. “In the middle of summer, when you had to lift the trays, there was always a chance of a rattlesnake underneath one of them. I only saw one, but there was always the possibility.”

A History of Fruit Dehydrators

Dehydrators gradually replaced much of this process, though even today, apricots, peaches, and nectarines are sun-dried. But certainly, with prunes, the dehydrator became the preferred method. “A dehydrator prune is 100 times better than any sun-dried prune;’ claimed Richard Nola. “When you put it in a dehydrator, you’re pulling the moisture right out of it, and it’s a much more sanitary product.”

Joseph Saito was on a ranch that had one of the first dehydrators. “You might still have the French prunes drying the first of October, and every time it rained, you were up in the middle of the night stacking the trays. With the dehydrator, this work was over. The dehydrator was fired from diesel fuel, and the timing was mechanical. With the dehydrator, you had to be careful. You could leave the fruit in there too long, or the temperature would get too high. Drying time and temperature depended on the moisture content of each load of prunes, so it was very easy to burn a carload. You put in your prunes, and in 24 hours, you take them out and end up with a clean product.”

Howdy Rogers explains the mechanics of his dehydrator.

“The original dehydrator was put out in 1917. It was all wood and an oil burner. You could put three or four tons of fruit in that one. The second one we got was in 1947. Most of that was a cement block and corrugated iron, which burned butane gas cheaper than oil. It could hold a lot more fruit, 10 tons. With that one, you’d stack the trays loaded with prunes on the rail cars. The tracks took the cars into the dehydrator. That one was 24 hours a day and had to be maintained day and night.”

The Moriel family also purchased a dehydrator early on. It had two tunnels. “My dad had one of the first dehydrators in Vacaville,” said Jim Moriel. “He was the largest prune grower in Solano County. It was very important to him to have quality fruit. Quality in terms of prunes generally meant size and how well they were processed in terms of drying. Before we got the dehydrator, he had his prunes dried by Sunsweet Dryers or with a person in Winters.”

Lola Nofuentes Moriel explained her husband’s dissatisfaction with that. “He used to get irritated because our prunes were ready to pick, and sometimes the dehydrators were full.” Jim Moriel also dried prunes for other farmers.

“My Husband Dried Burton Prunes For Jim Low. Low Didn’t Like The Way The Other Dehydrators Dried His. My Husband Had A Special Way Of Drying Them.”

Buck Burton added: “When you dry French prunes, you end up with mostly fruit. When you dry Burton prunes, you end up with prune juice running down and all over the door of the dehydrator. It’s just too much moisture. They did dry them, but it took over twice as long. You can dry French prunes in 24 hours or less. Burton prunes take 48 plus hours.”

Once the fruit was completely dried in the dry yard or the dehydrator, it had to be removed from the trays. At times, scraping them off the trays was hard work, as Jim Moriel recalled: “The apricots that taste the best are the ones that get ripe. They have lots of sugar. We called those apricots ‘slabs’. They were not able to maintain their shape. Instead of sustaining a nice round shape, they sagged, and the juices would seep out. Those were the hardest ones to scrape off because they would stick to the tray.”

How To Turn The Fruit In A Dehydrator

Farmers used scrapers, also called fruit paddles, to remove the fruit without damaging it. “They looked like flippers for flipping your eggs, a pancake turner about 8 inches wide by 6 to 8 inches;’ Ethel Hoskins said. “They could scrape under the fruit to loosen it and dump them in the lug boxes.”

The Meriel family had scrapers specially made. “You get a little garden hoe, about 18 inches long, take it to a welder, and they bend it to straighten it out so it is a blade for scraping. The size of a garden hoe is much wider than a regular scraper so that you can do a lot better job.” Richard Nola described the operation, too;

“You Take The Tray, One Person On Each Side, Tilt It On An Angle, And Push The Scraper Across The Top To Knock The Fruit Off Into Boxes.”

Once the fruit was scraped and loaded into the boxes, it was hauled off to storage.

“We had a warehouse with cement floors;’ Lola Nofuentes Moriel said. “You ensured the floor was clean because the health inspector used to come around. You’d dump the apricots into a pile, and we kept them there until the buyers would offer a price. Initially, you used to put them into burlap gunnysacks that weighed about 100 pounds. Later we used to deliver the bulk organic apricots in boxes.”

Dried prunes went through yet another process related to Howdy Rogers. “We had big wooden bins in the shed, and you put all those prunes there. There was no top to the bins. They were square with a bottom and sides. They say the prunes go through a ‘sweat’ inside the bins, equalizing the moisture, so all the prunes have the same moisture content. It doesn’t take long, but they could stay in the bins until near Christmas.”

Dried Fruit And The California Packing Corporation

In the late ’30s, Kirby Stevens worked for California Packing Corporation, which would eventually become the Del Monte Brand, which handled dried fruit. “It was a big three-story building between Fairfield and Suisun on Union Avenue. The nut and dried fruit farming came in from Suisun Valley, Vacaville, and Winters. They would come in with the dried fruit on trucks and we’d weigh it. Then we’d go out and take three or four samples and grade it.”

“These guys, some of them were pretty sharp. They’d put a bunch of slop down in the bottom of a box to get rid of it. You had to watch out for that. That was my job. Dig in and get to the bottom of the box and on the side where there might be a game being played on us. From there, the fruit was put into bins. As orders came in, they could be shipped anywhere in the United States in freight cars. The spur came right there.”

Most farmers don’t dry their own fruit anymore, and opinions vary about why they stopped.

Bill Robbins believes that food sanity regulations ended the practice. “Birds would fly over, so there were problems with bird droppings. The fruit is washed, but that wasn’t good enough for the government, so the home ranch dry yards were shut down. Eventually, all the fruit went to dry yards like German’s dry yard and Yee’s in Suisun Valley and Vacaville Fruit Company.”

Sue Grotheer Lippstreu believes the change had to do with economics. “We’d have all the prunes out to dry and rain would come. We’d be out all night stacking up fruit trays. Finally, my dad said he thought he could do it just as economically by having the commercial dehydrator do it.”

Electricity Needs For Housing And Farming In 1960s California

At the Rogers Ranch, encroaching housing developments with their high need for electricity became the problem. “We stopped sometime in the 1960s. The farm had a compressor that pumped in the air and then we had a thing chat pushed the cars through on the tracks. The train had to have a great deal of electricity for that.”

“We also had to have the motors to go in there to blow the air and circulate it. Come to find out, in the early morning, the power would go down and the compressor was out. I complained to PG&E. Someone counted the transformers from the city out towards us. There were so many that by the time it got to us, the juice was gone! Our guy was working up there at night and he couldn’t push the cars through. Every time, he was five or six cars shore. Well, the expense goes up. Then came Vacaville Fruit Company and which did a commercial job of drying. It was easier and cheaper to take it right to them.”

The Old Fashioned Way Of Drying Fruit

Still, some people never lose a taste for doing it themselves. Buck Burton is one of those.”We still dry a few apricots. We have one acre where we cut and dry just like they did a hundred years ago for a dry yard. The same trays and the same sulfur box.”

Today, the Vacaville Fruit Company dries, packages, and markets fruit for farmers nearby. Richard Nola bought the business in 1960.”Originally we had called it Vacaville Dehydrator. We changed it to Vacaville Fruit Company, which represented Vacaville’s heritage more.”

Investments In Modernizing Vacaville Farming

Through the years, Nola has modernized the plant. “The original dehydrator was built in 1944 by Danielson & Bowers. They had four dryers. With four dryers, you could run approximately eight tons a day. When I bought the plant, I put in two more dryers. A few years later, we built eight more dryers to make 14 total. Yet a few years later,

Del Monte Corporation Approached Me About Building More. I Put In Another 20. We Now Have 34 Units.

“The original building is 300 feet long and 120 feet wide, and they had a receiving barn, 80 by 40, where they stored the prunes. We gradually built more buildings. The dehydrators were added later. We built another shed and then another,” Nola said.

“In 1960, the property, 15 acres, was in the country. We have gradually been surrounded by housing. There are restrictions from the city regarding that we can only dry something where the smell is not offensive to the residents. We use water in the scrubbing system to remove the SO2 and keep it from entering the atmosphere. It goes through plastic piping, and we have a vacuum pump that moves it through the piping system into a tank of water so it won’t go into the atmosphere.

“We have two automatic cutting machines for apricots. We use them sparingly because the quality is not nearly as good as when you do it by hand, but they help with labor costs. Nectarines are all cut by hand. The automatic cutting machines will not handle a nice, soft, lovely peach, so they are cut by hand, too.”

A Standard Size For Fruit Equals A Standard Time For Drying

“At one time, prunes would last about 60 days because they had several varieties. That spaces it out. Now, it’s French prunes. Apricots ripen simultaneously, so you get a lot of apricots at once. We are only able to handle a certain amount of tonnage a day. What we can’t handle has to go into cold storage.”

Besides his dehydrator, Nola still runs a dry yard, where the fruit is sun-dried. “In the case of apricots, nectarines, peaches, and pears, if you go directly into the dehydrator with them, they do not look nearly as good as if you go into the sunlight. The sun’s ultraviolet light dispels the chlorophyll, or the greenness, and brings it to the surface. Lactone is the orange color you see in the apricot or the peach. Without going into the sunlight, you don’t get that transformation. And, of course, solar energy’s less expensive,” Nola continued.

The Use Of Sulfur Dioxide

“We use sulfur dioxide. The insects fly, and ants do not want to get close to it. We have our yards all graveled, so dust won’t blow on them. We use covers to keep the fruit clean. The apricots are left in the sun for one day or two. Pears one day. Then we dry it in the shade, meaning stacked up, and let it come down slowly, not exposed to the sun. Peaches, we leave three days in the sun and then stack. Then we put them in the dehydrator overnight.”

“In the original operation, all the scraping – removing the fruit from the trays – was done by hand. It was highly labor-intensive compared to the mechanical scrapers,” Nola explained.

The Process For Drying Of California Prunes

“For unsulfured fruits, such as prunes, the dehydrator makes a much better product than putting it out in the sun. If you go in the sun without the preservative, it takes a lot longer to dry, and it turns a darker color. In the dehydrator, you immediately expose it to heat, sealing it to maintain a lighter-colored product.

The Drying Process For Walnuts And Almonds

The walnuts and almonds produced in Solano County also go through a drying process. Neal Rotteveel grows almonds. “We shake the almonds off the tree and leave them on the ground to dry. After they dry, we bring them in for processing. The most moisture we like to see in the almonds is below 6 percent.

“We have a lot of equipment to take off the fore-material, the hulls, and then the shells. You wind up with a pretty clean product, what we call brown almonds. There are big rollers and the first roller hits the big almonds. If the meat comes out, it is directly separated. The almonds that are a little bit smaller go to the next rollers that are a little tighter and a little closer together. There are six or seven of those stages.

Once they crack, the meat gets separated. With this equipment, we’re getting a lot better finishing job than 20 years ago. Twenty years ago the big handlers, like Blue Diamond, had some sophisticated equipment, but in the last 10 years, a lot of handlers and the bigger growers have even better equipment than Blue Diamond to do the rough hulling and shelling. Every year we see more and more modern equipment coming out. There are manufacturers, but mostly the ideas come from the bigger growers, who see ways to streamline their operation or come up with a better end result.

Different Sizes Of Almonds

After the meat is separated, the almonds come through screens and are separated by air. They come in bins of all different sizes. We run them over screens again and size them what we call size index. We separate them into large, medium, and small. The shell size may have nothing to do with the almond size. If we have 16-18 almonds, or 20-22s, that means there are so many almonds per ounce. Alternatively, if you have 18-20, that’s 18 per ounce. Then, if you have 22s, it would be 22 almonds per ounce. If you have the 30s, the almonds are much smaller because you have 30 almonds per ounce. It goes all the way up to 36. So you have sizes from 16 to 36.

Blue Diamond sells them that way. Usually, the larger the almond, the more money it will bring. But sometimes, the small ones will bring more money because the candy manufacturers use them. Blue Diamond is very particular about size.

‘The final stages are sorting by the human and electronic eye,” he continued. “Going through the equipment, we can get some slight damage; the brown skin comes off or is chipped. We don’t want any damage if we are talking about top-grade almonds. Electronic sorting machines detect a white spot or damage, and those almonds are thrown out immediately:’ Rotteveel has expanded over the years and now does processing for other growers. “They do their cracking, but we do the final processing and marketing,” he said.

The History Of Hulling Walnuts In California

Arlene Samuels grows walnuts, which need to be hulled. This process has a long history on the Samuels Ranch, which Samuels first witnessed as a young bride. “When I first moved up here, the biggest shock was to see Shad’s mother with a box of walnuts taking the hulls off by hand. If they were too hard to the hull, they took them down to a company in Vacaville and had them done.

“When we bought the place 35 years ago, my husband, Shad, got a two-ton huller. In the orchard, the walnuts are put in boxes, loaded on the jeep, and hauled over to the huller, where they are stacked until we get enough to pull them and put them in the dehydrator and not waste propane.”

The Process Of Cleaning Walnuts

“No one likes the hulling. Even with machinery, you’re still lifting boxes. You have to pour the walnuts into the huller – a funnel-like thing. These bulk walnuts run through water and a basket-like thing that rotates around and around and has what they call ‘knives,’ wires that stick out. Those wires take off the husks. Then the walnuts are washed and down onto a tray.”

At this point, the walnuts are sorted. ”As they come down, we’re sorting them as quickly as possible,’ Samuels continued. “Not all of them get their hulls off. The Eurekas are hard walnut to get the hides off because they are pointed and do not do as well going through the huller. You also sort for bad walnuts,’ she added.

Once they are hulled, the walnuts are ready to be dried. “Traditionally, we dried the walnuts on trays, but we didn’t put them out in the sun because that sometimes will cause them to crack. Walnuts, if you have moistness, the outer shell will crack. They don’t like cracked shells when you go to sell them. We would stack the trays on top of each other and put little pieces of wood in between so there was a crack in between the trays for the wind to go through,’ Samuels said.

On the ranch John Lowe farmed the walnuts were dried in this manner. “It would take two weeks to dry the walnuts, depending on the weather,” he said. “You could tell when they were dry because the shells turned lighter.”

Technology Changes Bring In Industrial Drying Of Nuts And Fruits

The old way of drying changed for the Samuels when they purchased a dryer. After being hulled, “The walnuts are then put in clean boxes and hauled over to the dehydrator,” Samuels said. “We walk out on what I call the catwalk and dump them into the dehydrator. The dryer runs on propane. Depending on how green the walnuts are, It takes two or three days to dry a batch. The dryer has made things easier because walnut trays are hard to work with. You have to wash them, and they get heavy as you lift them to dump the walnuts off them into boxes.”

Instead of propane, Frank Buss uses hot air to dry his walnuts. “The dryer is a box-like arrangement with a blower on it,” said Buss. “We have two of them. They dry for about 500 pounds. They can dry 600 pounds, but we try to put only 500 pounds in each one. We only have a couple of tons, so that’s only four times. It takes about five days for good drying. All you do is blow air through them. Many of the factory ones use diesel fuel to fire the burner. Then they can dry them in 24 hours, maybe a little more. We do the air because we have the time to do it.”

He Continued, “You Separate The Walnut Varieties When You Dry Them. The Walnut Buyer Likes To Know What He Is Going To Sell.”

They pay you less money if you have mixed walnuts. It was always necessary to be sure that you had the Serrs, Franquettes, Eurekas, and Hartleys in their separate bins.”

Buck Burton may dry his own apricots, but his whole walnuts are dried commercially. “We put the walnuts in a trailer that has a false bottom. The trailer holds about five or six tons. There’s a solid bottom to the trailer, and then there’s a little rack and a screen bottom so that the air can go through. You hook a heater with a big fan and blow hot air into this space under the walnuts. The hot air naturally goes up through the walnuts and dries them. It’s a neat process.”

Sue Grotheer Lippstreu – A Service Of Hulling Walnuts

Since the co-op will not take walnuts unless they are hulled and cleaned. Sue Grotheer Lippstreu provides a needed service by hulling walnuts for other farmers. “I use 20 to 25 men in walnut harvest because I have my dehydrator for walnuts. I not only dehydrate my walnuts on this ranch, but I dehydrate for a bunch of other farmers in Suisun Valley. They bring them here, and we process them. We take that green husk off the top. We sort them and take out the bad ones.”

The dehydrator was built by her father around 1950. “He designed that whole dehydrator,” said Lippstreu.”I marvel at that man. How to put the underground tunnels. To get the copper heating. Then attach the units. You should see it run. You would wonder how anyone could figure it out.”

Words From Kristin Delaplane, Sabine Goerke-Shrode, And Philip Adam. For Solano Gold – The People And Their Orchards At The Vacaville Museum.