Your cart is currently empty!

The History Of The American Cranberry Farming industry

Out of acidic streams and sandy soils, cranberry farmers have built intricate waterways and fertile bogs. Cranberry agriculture is perhaps the best example of the resourcefulness and judicious adaptation that characterize Pineland’s folklife.

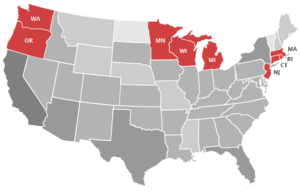

The history of the development of the industry is a story of environmental recycling. The American cranberry (Oxycoccus macrocarpus) is a vining evergreen that grows naturally in sandy, swampy areas of eastern Massachusetts, the upper Midwest, and southern New Jersey. Its fruit ripens in the early fall and can be stored until spring. Natives gathered wild cranberries regularly before the 18oos. The first cultivated cranberry bog in the Pines was planted in the 1830s by Benjamin Thomas at Burrs Mill in Southampton Township.

In 1857, James A. Fenwick purchased the 108 acres that would become the nucleus of the Whitesbog agricultural plantation. He was recycling the water supply and workforce from the nearby Hanover Furnace. Mary Ann Thompson points out that the bogs are “remodeled cedar swamps.” They are water, turf, and cedar components, which became reservoirs, roads, and floodgates.

Whitesbog, New Jersey Grows to Be The Largest Cranberry Bog In The U.S.

Eventually, Whitesbog would encompass 3,000 acres, most purchased between 1884 and 1909 by Joseph H. White, Fenwick’s son-in-law. At this time, Whitesbog consisted of cranberry farming bogs, blueberry fields, and a water supply system at the height of its development. The village of Whitesbog grew up around the sorting house and the migrant workers’ villages of Florence and Rome, named in honor of the immigrant Italian workers.

Four parallel streams that flow from east to west into the Rancocas Creek, a tributary of the Delaware River, provided the water supply for Whitesbog. Gaunt’s Brook and Antrim’s Branch are located to the north, and Cranberry Run and Pole Bridge are to the south. To the east and west are swamps. The main water supply came from the Upper Reservoir. The second water supply system was created by damming the Pole Bridge Branch to form Canal Pond.

Man-Made Bogs Built In New Jersey

Between 1857 and 1912, 40 bogs covering 600 acres were designed and built at Whitesbog. Lower Meadow Bog, Old Bog, and Little Meadow Bog were the original bogs built by Fenwick. White built five other groupings of bogs, named the Cranberry Run Bogs, the Ditch Meadow Bogs, the Pole Bridge Bogs, the Upper Reservoir Bogs, Antrim’s Branch Bogs, and a grouping consisting of Big Swamp Bog, Billy Bog, and John Bog. Today, it is more common for the bogs to be numbered. Subsequently, in the early twentieth century, J. J. White helped develop the adaptation process to an art. In his manual on cranberry culture, he sketched out the recycling of “muck” into bogs.

Over the years, even the wild vines have been given a second life as growers continue hybridizing them. Sowing their identity into the fruit with names such as Howard Bell, Richard, Garwood, Bozarthtown Pointer, Braddock Bell, Applegate, and Buchalow. The engineering of land and water basic to cranberry farming begins with a location on a good water supply. Importantly, most planters seek a ten-to-one ratio of headlands, or upland water supply areas, to bogs.

How The Water Flows In 2024

Today, each cranberry plantation in the Pines is located on a branch of a major waterway. A system of reservoirs, dams, canals, and dikes connects the bogs with the main water supply. Specifically, this system acts as valves and pipes, which can be regulated as necessary with the farmers’ built gates.

The bog is a symmetrical and precise structure, and the Pines’ present bog landscapes represent many lifetimes of work. Today, cranberry farmers assess the fine points of various bogs and bog-building techniques. Referring to some bogs, such as Buffin Meadows, at the Darlington plantation, as “state of the art.”

Efficient Water Management

As cranberry farmers Stephen Lee and Henry Mick described, building a bog begins with planning for efficient water management. The land’s topography is first surveyed near a stream, and the reservoir is at the highest point. The area in which the bog was built was either scalped of vegetation or flooded to kill vegetation. Today, the trees are usually removed with heavy machinery and useless vegetation is burned off. Cedar and pine are kept for gates and equipment, cedar for things to be partly submerged, and pine for full submersion. Irrigation channels, consisting of a main center ditch with perpendicular side ditches, are used in older bogs.

Today, underground pipes have a use in irrigation. A dike surrounds the bog. It is made of a sand core from the ditches dug around the bog. Then, it is covered with turf cut from the bottom of the bog to prevent erosion. These dikes also serve as narrow roads between the bogs. Wooden gates at key places in the dike walls control the water flow.

Bogs Are Being Built With Water Conservation In Mind

The bottoms of older bogs may be uneven and rough compared with those of recently built bogs. Today, bogs are graded to be within a half inch of level for water conservation and ease of harvest. Subsequently, it may take three years to build a bog and several more to develop the plants. Even then, a bog, like a house, may “settle” in places within the first year or two and require regrading. Most new bogs are planted with cuttings from other bogs. A cover of sand is spread over the muck at the bottom of the bog. The vines are inserted in small holes in a grid pattern made with a long-handled tool, sometimes called a “dibble.”

Water is essential to cranberry farming, not only as sustenance but also as protection. Thus, water levels in the bogs respond to both regular growth cycles and irregular temperature fluctuations. The “winter flood” protects vines from the cold of winter months, and the “spring draw” uncovers them for the growing season. At full fruition, the “fall flood” buoys the fruit for easy harvest. In between, water may play havoc if it turns to heavy ice, chokes off oxygen, or when rainstorms inhibit pollination. Moreover, unseasonable drops in temperature can damage uncovered vines. According to Stephen Lee, Jr., “You don’t plan to do anything in the evening during frost season. You have to watch the thermometer.”

Managing these floods and surveilling the dikes is entrusted to a “water foreman.” Undoubtedly, their credentials usually include mental maps of complex water systems compiled through a lifetime of living in the Pines. Cranberry farmers have a history of independently crafting technology for their small, rather esoteric branch of agriculture.

The Invention Of The Cranberry Scoop

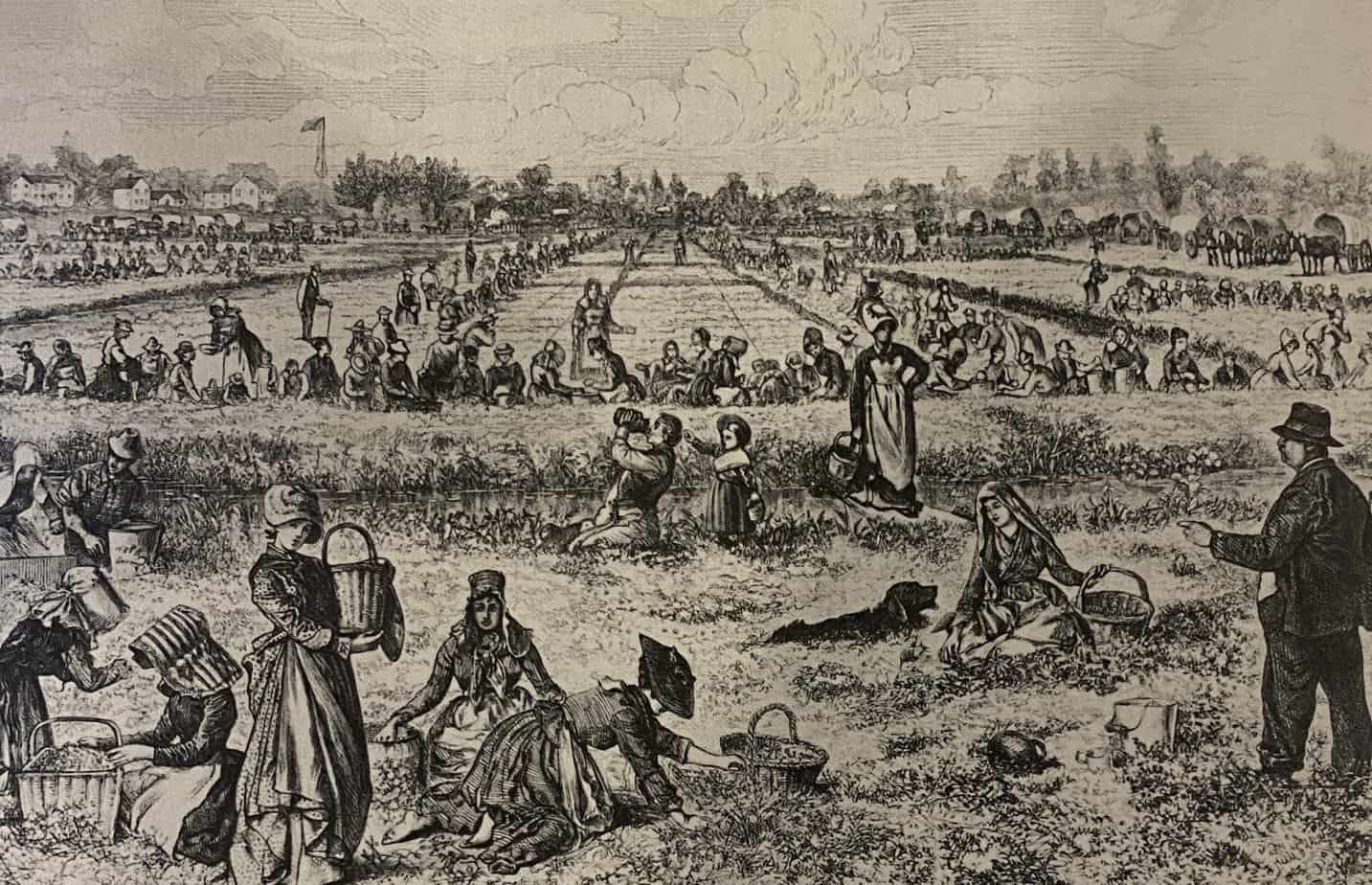

In the early twentieth century, the cranberry scoop was introduced in the Pinelands. The Makepeace scoop, which came from Cape Cod, and the Applegate scoop, designed by David Applegate of Chatsworth, provided the types on which other local scoop makers worked many variations. The scoop is a wooden box with one open side. Using the scoop requires bending low to the ground and “combing” the vines with light, short strokes that do not tear the vines as the berries are pulled off. The operation was carried out as Doughty described, with scoopers strung across the bog, each worker having a one-peck box. When the box was filled, he would dump it into a one-bushel packing box and then receive payment.

Cranberry scoops were used until the 196os, and they have now joined the ranks of other utilitarian objects, such as the decoy and the sneakbox, which have become aesthetic symbols of place. Joe Reid, whose wife, Gladys, is the grand-niece of David Applegate, makes replicas of the scoop to be used as flower holders and magazine racks.

Mark Darlington, great-grandson of J. J. White, says his father, Tom, can remember “back in the very old days” when everyone was on hands and knees raking with their fingers. Cranberry scoops represent a variation on that theme, as do many of the automated dry-pickers found a use in this century. They include one his father designed: “The way we picked these, now, before the wet-harvester became available, he had a small machine about the size of a desk that you walked behind that had rows of cones that would work in a dry bog, and it would sort of rake through the vines and flop up in a rotating bucket arrangement and then dump ’em in a bag in the back.”

Modern Innovations In Cranberry Farming Techniques

Today, only a few growers use dry harvesting because it is less efficient, more time-consuming, and more destructive to the vines than wet harvesting. However, dry-harvested berries are preferable for fresh sales, so there is still a market for them. In the early 196os, the “wet method” of harvesting cranberries was developed. The fields will flood at least two inches above the top of the vines using special machines. “Walk-behinds” or “Ride-on” agitate the vines, knocking the berries off. When cranberry farming captures the berries floating to the surface and are “hogged,” or gathered, toward a conveyor belt that moves them onto a truck.

Cranberry Farmers Will Share A Single Wet Harvester Machine

The wet harvester is the subject of endless improvisation and adaptation, which Darlington describes as “sort of a communal project.” Because there are not enough farms to make the development of special cranberry machinery worthwhile to companies such as John Deere, the cranberry farmers pool their resources. Exercises with ingenuity involve the adaptation of other purpose commercial machines. Abbott Lee developed a cranberry pruner by adapting a John Deere Model 640 rake.

The Packing House

The packing house is the focal point of a cranberry plantation and the final point for technological innovation, set within a traditional frame. In the nineteenth century, harvested cranberries were transported from the bogs to the packing houses in covered wagons. The packing house was often located in a town, such as Medford or Vincentown, far from the bogs.

Later, as the workforce grew, so did villages, such as Whitesbog and Double Trouble, near the bogs and around the packing house. In the nineteenth century, cranberries were harvested by local families. By the turn of the century, however, growing manpower needs brought about the recruitment of Italian and Jewish workers from Philadelphia.

The cranberries will confront their separation from the chaff at the packing house. Then, sorting by machines that operate on a “bounce” principle: good berries bounce; bad ones don’t.

Sorting machines bounce the berries as many as seven times. Legend has it that the bounce principle was discovered by ‘Peg Leg’ John Webb when he dropped a box of berries at the top of a staircase. A final sorting under sunlight was done before the berries were packed for shipping. The barrels are emblazoned with the special label of the grower.

Often, the label carried family nicknames. The American Cranberry Exchange classified berries and often assigned names of indigenous plants and places. These would appear on the label, also. The traditional structure of packing houses evolved to accommodate these tasks. Their high-peaked, multi-windowed buildings allowed maximum light and ventilation.

The Automated Cranberry Operation

The bulk cranberries arrive in trucks today and depart in large, square boxes. In between, they must still be cleaned and sorted. Local ingenuity continues to rework machines to bounce the berries. The development of cranberry farming agriculture dramatically affected the Pinelands population.

With the influx, villages grew up near the bogs. In recent times, however, the practice of housing migrant workers has given way to the hiring of day labor. Migrant blacks, Puerto Ricans, Haitians, and Cambodians have all worked the bogs, along with Anglo natives of the region. Many Puerto Ricans who used to migrate to the bogs have now settled into permanent communities at Woodbine, Hammonton, and Vineland. With the natives, they form the core of experienced bog workers.

George Marquez And Orlando Torres: The Lives Of Puerto Rican Agricultural Workers

Mr. Marquez has worked for 20 years or more at the Birches Road Cranberry Farming Bogs in Tabernacle Township. He found the job through a friend at the agricultural employment office. When he started, he told folklorist Bonnie Blair, he drove about 30 workers daily in a bus from Philadelphia. They hand-harvested cranberries using scoops. Only four or five of them were Puerto Rican. Today, Marquez lives in Philadelphia. He works in the cranberry packing house only during September and October, using vacation time from his regular job in Philadelphia to work in New Jersey.

Orlando Torres was born and raised in Chatsworth and now lives with his wife Hazel in Vincentown. His father was a crew foreman at the Haines’s Cranberry Bogs, and he began working in his father’s crew. Eventually, he became a crew foreman because he could speak both Spanish and English.

Most of Torres’s crew are seasonal workers. They work for six months in New Jersey, picking blueberries in the summer and cranberries in the fall, then returning to Puerto Rico. In Chatsworth, however, there is a permanent Hispanic population, which includes Torres’s parents. Though his parents think of themselves as “Puerto Rican,” Torres thinks of himself as a “Piney,” a sentiment he proclaims on his “Piney Power” cap. He explained his feelings about the Pines to folklorist Bonnie Blair by comparing himself to the bird that leaves its nest before its time and will always return. He says, quoting his father-in-law, “You can take the Piney out of the Pines, but you can’t take the Pines out of the Piney.”

Families In Cranberry Bogs

The cranberry families have created communities. At the center of the community of the growers are the families, many of which involve several generations working together. Often, different aspects of the business are divided among members. Family members often form the core workforce in cranberry farming bogs all over the northern states of America.

Many thanks to the collection Pinelands Folklife Project.